London (Washington Insider Magazine) – Political polarisation has intensified across multiple democracies in recent years, driven by ideological divides, affective partisanship, economic pressures and the spread of misinformation, according to academic research, policy studies and international monitoring reports. Governments, international institutions and technology platforms are responding with measures aimed at safeguarding democratic processes, but evidence shows that partisan animosity and fragmented media environments continue to erode trust in institutions. Rising support for far-right and other anti-establishment parties, contentious election cycles and recurrent protest waves have contributed to a more confrontational political climate in regions including Europe, the Americas and parts of Africa and Asia. Researchers warn that these trends are affecting democratic accountability, social cohesion and policy-making capacity in states facing simultaneous security, economic and public health challenges.

The current phase of political polarisation is characterised by both ideological distance between parties and “affective polarisation”, where citizens increasingly view supporters of rival parties with hostility. Studies of party systems, electoral behaviour and media consumption patterns show that political identities have become more central to social and cultural life, often shaping perceptions of news, public policy and even personal relationships. Scholars describe this environment as one in which partisan affiliation can operate as a primary social marker, influencing trust and interaction across communities.

Polarisation and democratic institutions under pressure

Researchers and policy institutes report that heightened polarisation can weaken core democratic functions, including compromise, oversight and accountability. When parties and voters see opponents as illegitimate or dangerous, cross-party bargaining becomes more difficult and electoral competition may focus increasingly on mobilisation through negative campaigning rather than policy alternatives. Political scientists examining recent election cycles note that “negative partisanship” – voting primarily to oppose the other side – has become a significant driver of turnout and party loyalty.

In the United States, decades of partisan sorting have produced sharply divided party coalitions along ideological and demographic lines, contributing to gridlock and confrontational legislative politics. Academic analyses of the 2020 presidential election describe it as part of a longer period of “hyperpartisan” competition, with each major party increasingly reliant on distinct geographic, socio-economic and cultural constituencies. Studies warn that in such contexts, efforts to hold leaders accountable for performance can be undermined if partisan loyalty outweighs evaluations of policy outcomes or governance quality.

Across the European Union, international security and economic think tanks report that internal polarisation and the rise of illiberal and populist movements are straining the bloc’s capacity to agree on common policies. The Munich Security Report for 2025 concludes that growing ideological divides and the advance of far-right parties have complicated decision-making on issues ranging from fiscal policy to foreign and security strategy. Analysts note that these trends have affected major member states, including France and Germany, contributing to fragmented parliaments and coalition negotiations in which policy compromises are harder to reach.

Economic pressures, protests and polarised contestation

Economic stress, perceptions of inequality and concerns over corruption have repeatedly intersected with polarised politics in recent years, according to protest tracking and risk assessment projects. Carnegie’s Global Protest Tracker recorded a high frequency of significant anti-government demonstrations worldwide during 2019 and 2020, often centred on grievances such as corruption, electoral manipulation, public service delivery and police violence. Researchers observed that many protests continued despite the public health risks associated with the Covid‑19 pandemic, indicating strong underlying discontent.

In its 2024 edition of the Social Resilience Index, Allianz reported that a “super electoral year” involving more than 70 countries saw incumbent parties in developed states lose vote share and recorded a shift to the right in the ideological centre of gravity in 16 European countries and the United States. The report stated that increased partisanship and polarisation were weakening trust in institutions and markets, with potential implications for investment, social stability and long-term growth. It identified polarisation as a factor that can affect social resilience by reducing willingness to compromise on reforms and undermining confidence in collective problem-solving.

The peace research group Vision of Humanity noted that 2025 began amid a renewed wave of political disruption, linking protests and contentious politics to economic challenges including inflation and inequality as well as to geopolitical tensions. Its analysis highlighted that such conditions can exacerbate social divisions and provide fertile ground for polarising rhetoric and mobilisation. Observers have documented examples where economic grievances are channelled through competing partisan narratives, further entrenching political divides.

Social media ecosystems and the spread of misinformation

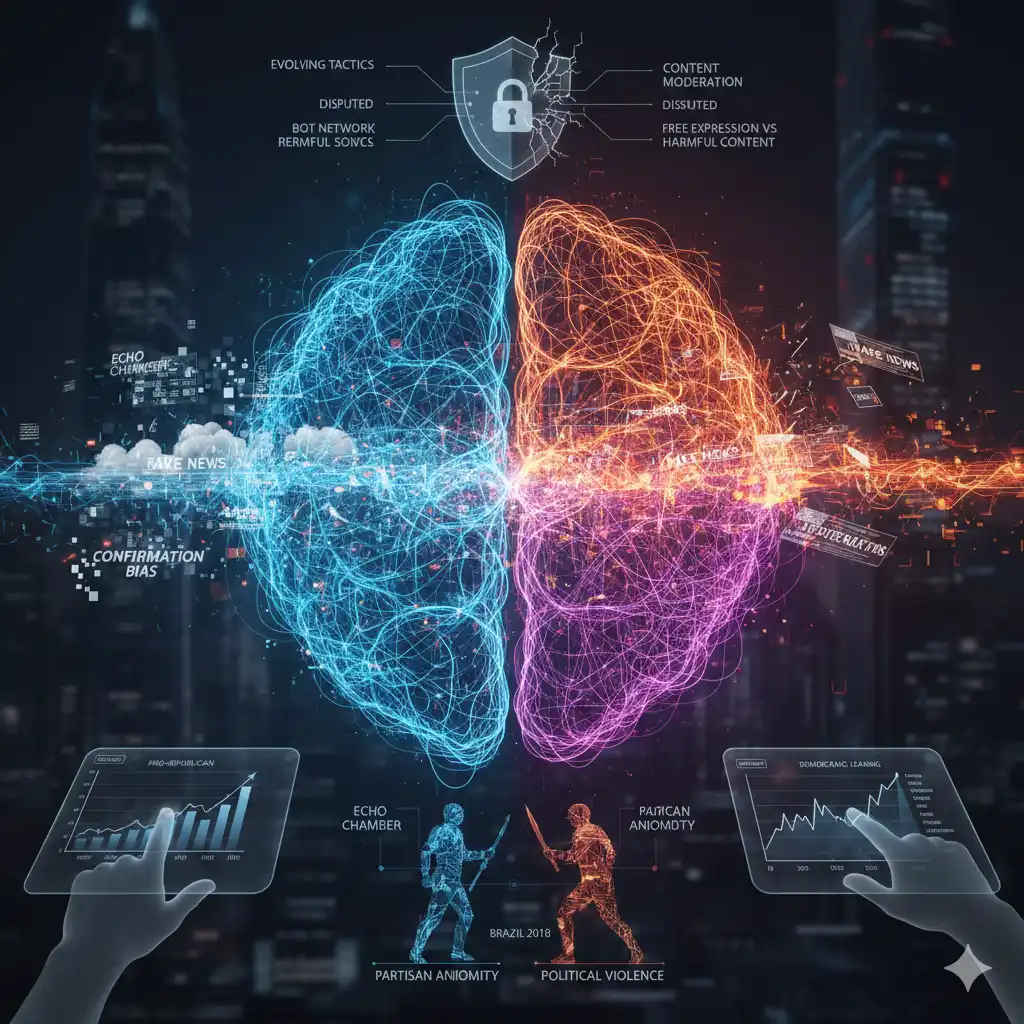

Media studies and communications research show that changes in the information environment are closely associated with political polarisation trends. Traditional and digital media outlets, including algorithm-driven social platforms, have enabled audiences to select news aligned with their existing beliefs, reinforcing “echo chambers” and confirmation bias. A study published by the Brookings Institution found that exposure to fake news on social media was strongly correlated with users’ partisan networks and levels of animosity toward opposing parties.

According to the Brookings analysis, users whose feeds were dominated by pro-Republican accounts in the United States consumed a significantly higher ratio of fake to mainstream news compared with those connected primarily to Democratic-leaning accounts. The study concluded that political partisanship and particularly hostility toward the other party were strong predictors of sharing fabricated news stories, whereas measures of general political knowledge and cognitive reflection were less strongly associated. Researchers interpreted these results as evidence that polarisation itself can drive the spread of misinformation, rather than misinformation simply causing division.

Academic and policy reports also document how social media has influenced electoral campaigns and political violence in other countries. Analyses of Brazil’s 2018 elections describe an environment of “hyperpolarisation” in which social media platforms were used to disseminate misleading or false information that amplified tensions between rival camps. One study cited the use of encrypted messaging services and online platforms to circulate disinformation supporting candidates and to sustain highly partisan communities, including in some cases incidents of politically motivated violence.

Specialist outlets and research institutes note that major platforms have introduced content moderation measures and initiatives aimed at reducing the visibility of false information, automated accounts and coordinated inauthentic behaviour. These steps have included labelling disputed content, removing certain bot networks and adjusting algorithms to promote more authoritative sources. However, policy papers observe that polarisation and disinformation remain significant challenges, with evolving tactics by political actors and difficulties in balancing free expression with the mitigation of harmful content.

Affective polarisation and social relationships

Scholars describe a distinction between ideological polarisation, which focuses on policy disagreements, and affective polarisation, which refers to how much partisans dislike or distrust the opposing side. Research indicates that affective polarisation has risen markedly in several established democracies, with party identification increasingly influencing interpersonal attitudes and everyday social interactions. Studies cite survey data showing growing reluctance among some citizens to engage with, or in some cases even live near or form close relationships with, supporters of rival parties.

A paper referenced in a 2024 commentary on democratic backsliding notes that party affiliation in the United States has become a “litmus test” in some contexts, shaping family dynamics and community relationships. The same commentary argues that social media can intensify these patterns by allowing individuals to curate ideologically homogeneous networks and by reinforcing narratives that cast opponents in negative terms. Policy research suggests that such affective polarisation can reduce trust in out-groups and further complicate cross-party cooperation on public issues.

Political science studies link affective polarisation to electoral strategies based on mobilisation against perceived threats from the other side. Analyses of recent American elections emphasise that both major parties have used negative campaigning and appeals to partisan identity to increase turnout among core supporters. Researchers suggest that this pattern can entrench long-term realignments within party coalitions, as groups respond more to narratives of conflict and grievance than to policy detail.

Regional variations and global implications

While polarisation is widely reported, researchers note that its causes, intensity and consequences vary across regions and political systems. In some countries, polarisation is primarily ideological, reflecting deep differences over economic models, cultural values or the role of the state. In others, it is linked to long-standing ethnic, regional or religious divides, and can interact with institutional weaknesses, including limited judicial independence or restrictions on media freedom.

Within the European Union, the Munich Security Report highlights that polarisation and the growth of parties critical of liberal democratic norms have affected debates over migration, climate policy, fiscal integration and relations with external powers. The report states that internal divisions risk constraining the EU’s response to security challenges such as Russia’s war against Ukraine and to economic competition from other major economies. It also notes that changes in the approach of key international partners can further influence internal dynamics by encouraging nationalist or unilateral strategies.

Global indices tracking democracy and conflict have identified links between polarised politics and risks of institutional erosion or instability. Policy papers caution that polarisation may contribute to democratic backsliding if it leads to the delegitimisation of independent institutions, acceptance of executive overreach or reduced tolerance for opposition. Monitoring organisations point out that contested elections and allegations of irregularities can generate cycles of protest and counter‑mobilisation in polarised societies, raising the potential for prolonged stand‑offs or sporadic violence.

Efforts to address polarisation and strengthen resilience

Governments, civil society organisations, researchers and international bodies have developed various initiatives aimed at mitigating polarisation and improving social resilience. These include reforms intended to enhance transparency, counter corruption and strengthen electoral integrity, as well as programmes that encourage cross‑group dialogue and media literacy. Policy institutes argue that measures enhancing trust in institutions, such as independent oversight bodies and clear rules for campaign financing and digital political advertising, can help manage polarised competition within democratic frameworks.

Some democracies have explored institutional mechanisms designed to reduce incentives for extreme polarisation, including proportional representation systems, independent redistricting commissions and multi-party coalition arrangements. Comparative studies suggest that electoral systems and constitutional structures can influence how polarisation manifests, with some models encouraging broader coalition-building while others foster binary contests. Researchers stress that there is no single template, but highlight that inclusive processes and credible institutions are important in maintaining legitimacy during periods of intense political disagreement.

In the media sphere, experts recommend continuing efforts to promote factual reporting, diversify news exposure and support independent journalism as means of countering disinformation and reinforcing shared baselines of information. Studies underline the role of public interest media and fact‑checking organisations in providing verifiable information during contentious elections and crises. At the same time, analysts note that responses to polarisation require sustained engagement across political, economic and social domains, given the multiple factors identified in current research as contributing to deepening divides.